Pages

|

Popular discourse within Japan and stereotypes of the Japanese by outsiders portray Japan as an ethnically homogenous society. Such a characterization contributes to the image of Japan and Japanese culture as unique. Thus, in the 1970s and 1980s a plethora of books and articles was published which extolled the alleged uniqueness of Japanese culture. These writings became known as the nihonjinron (“theories of Japaneseness”) literature, and the popularity of these writings led to a “nihonjinron boom.”

In the 1980s, Prime Minister Nakasone made a comment that echoed the sentiments of nihonjinron. He attributed the Japanese postwar miracle to the harmony that derives from a homogenous society. In so doing, he was contrasting Japanese homogeneity and harmony to America’s alleged heterogeneity and divisiveness, and he was suggesting that America’s economic problems during the 80s, as well as Japan’s economic successes during that time, stemmed precisely from the two countries’ opposing cultural traits.

Sparks flew. Many Americans criticized Nakasone, asserting that he misunderstood the fact that America’s diversity was precisely its strength. Many Japanese also criticized him, especially representatives from various ethnic groups. The upshot was that this event and others in recent years have made it increasingly clear that Japan is not as homogenous, or as unique, as the nihonjinron literature and popular discourse would lead us to think.

In fact, there is considerable ethnic diversity in Japan today. Minorities include over 600,000 people of Korean descent who are either Japanese citizens or permanent residents, as many as 400,000 Chinese, and an assortment of other Asians and Westerners. There is also an aboriginal group living mainly in Hokkaido -- the Ainu. There is also the burakumin -- a group considered racially Japanese but still discriminated against because of their descent from outcasts who were shunned because of their involvement in ritually polluting activities.

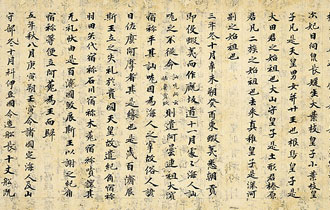

Because the Ainu, the burakumin, and many people of Korean descent living in Japan are Japanese citizens, i.e., are Japanese in the full social and political sense, it is important to avoid terms in referring to these various ethnic and other groups of Japanese citizens that suggest that they are anything less than Japanese. Thus I will use the terms Yamato Japanese, Ainu, burakumin, and Korean-Japanese rather than majority, mainstream, or minority in referring to the different ethnic groups of Japan. The Yamato Japanese are the descendants of people assumed to have followed the first emperor when he led them to the Yamato Plain in the Nara–Kyoto region and created the Japanese “nation” in BCE 660, as described in the Kojiki, the ancient mythology. Further, there are many permanent residents and other foreigners living in Japan who also must be considered in any discussion of ethnic diversity in Japan.

The Yamato Japanese constitute well over ninety percent of the inhabitants of Japan. Therefore, in a statistical sense it is appropriate to refer to them as the majority, and the other ethnic groups as minorities. However, to the extent that “minority” also implies a second-class citizen, it is a term that I choose not to regularly use in this essay.

However, I recognize that in the power structure of the society, these non-Yamato ethnic groups are generally at a significant disadvantage, as is typical for minorities everywhere.

Pages

|