Pages |

Teresa Morris-Suzuki says of the law:

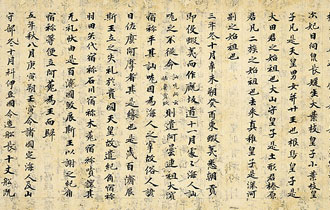

The tradition by which the village controlled farmland and had the power to redistribute it from time to time among inhabitants was replaced by a system of individual property rights vested in the heads of households. . . . This removed some of the arbitrary and oppressive aspects of the old regime, but opened the way to the rapid consolidation of farm holding in the hands of landlords, many of whom . . . were Japanese merchants (Morris-Suzuki 1998, 27).

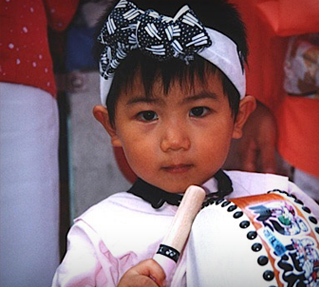

The Japanese government also embarked on a policy of cultural assimilation in Okinawa during this same period, paying particular attention to discouraging the use of the native Okinawan language and enforcing the use of standard Japanese among schoolchildren.

Japanese officials and intellectuals universally treated the Ainu and Okinawan cultures as primitive and uncivilized, thereby justifying assimilation policies as a way of "raising up" the native populations. However, because of supposed evidence of Ainu contribution to the ancient Jōmon culture of Japan, and because of the relationship of Okinawa's language to Japan's ancient language, some also thought of these peoples as representations of Japan's antiquity. The Ainu and Okinawans could thus be viewed simultaneously as Japanese and non-Japanese-as timeless pools left behind by the mainstream, as if "marooned in some earlier phase of national history" (Morris-Suzuki 1998, 31).

Factors in Japan's Late Meiji Imperial Expansion

While the securing of the peripheral islands of the Japanese archipelago was done at the expense of relatively weak indigenous peoples, any further growth would have to come at the expense of established East Asian states and/or Western colonial powers. Despite the dangers, leading Japanese intellectuals and government officials in the 1880s and 1890s began to support the idea of winning control over neighboring regions. Three factors were responsible for this drive: a nationalist desire for equality, desire for access to the raw materials and markets of East Asia, and strategic needs.

The first was the nationalist desire for equality with foreign powers. A colonial empire was seen by many as a mark of becoming a "first-rate" modern country—a label many Japanese desired. An example of this inclination was a memorandum by Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru in 1887, in which he pointed out to his colleagues the Western powers' rapid division of the world into colonies and the need for Japan to get into the game. He concluded,

In my opinion, what we must do is to transform our empire and people, make the empire like the countries of Europe and our people like the peoples of Europe. To put it differently, we have to establish a new, European-style empire on the edge of Asia (Myers and Peattie 1984, 64).

A second factor was the economic benefit of gaining secured access to the raw materials and markets of East Asia, which could be lost if another Western power gained control of the regions first. In the 1880s and 1890s, the Meiji political leadership saw industrialization as the key to national strength, yet the domestic market by itself was not yet strong enough to make large-scale industry profitable. The Japanese leaders hoped that the huge China market would spur development of their industries, if only they would be allowed in. Koura Juntarō, a leader in the Foreign Ministry, stated in an inter-departmental report in 1895,

Pages |