Pages |

The territory of China is vast, her people are numerous, and her resources not inconsiderable. If our marine products and manufactured products are to have one great market in the future, then we must take this opportunity to expand our commercial privileges [in China] (Myers and Peattie 1984, p. 135).

Peter Duus, in a study of the Japanese business community, concluded that they largely supported the expansionist policies of the government:

"Until the end of the Russo-Japanese War (1905) big business leaders and the highest echelons of government were moving on parallel tracks in their assessments of the economic future, their evaluation of an expansionist foreign policy, and their sense of economic promise in Asia. . . . Both government leaders and businessmen were responding to the same situation with shared attitudes (Myers and Peattie 1984, 146)."

More than any other factor, however, the political instability of China and Korea and the concerns the Japanese leaders had for their own country's security were the primary motivations for imperialist expansion. Unlike the Western powers, whose empires were in distant continents, Japan would expand in regions adjacent to itself in East Asia. As Mark Peattie has noted,

"No colonial empire of modern times was as clearly shaped by strategic considerations. . . . Many of the overseas possessions of Western Europe had been acquired in response to the activities of traders, adventurers, missionaries, or soldiers acting far beyond the limits of European interest or authority. In contrast, Japan's colonial territories (with the possible exception of Taiwan) were, in each instance, obtained as the result of a deliberate decision by responsible authorities in the central government to use force in securing territory that would contribute to Japan's immediate strategic interests (Duus 1988: 218)."

Japanese leaders in the 1880s and 1890s were well fully conscious of the fierce competition among powers for position in East Asia. They saw the declining fortunes of the Chinese and Korean courts as potential opportunities for Western intrusion. Preventing a third country from taking control of Korea became a chief concern in Japanese foreign policy. The Prussian advisor to the Meiji government coined a phrase which was repeated endlessly in the period: that the Korean peninsula was "a dagger thrust at the heart of Japan." Japanese officials and private interests therefore took it as their natural right to intrude in Korea's internal affairs.

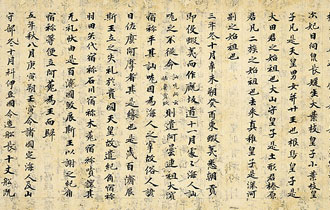

As Korea had for centuries been in a tributary relationship with the Chinese regimes, jockeying for position in the peninsula between Japan and Qing China in the 1890s soured relations between those two countries. War broke out in August 1894, and by April 1895, the Japanese military overwhelming defeated the Chinese army and navy. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ended the war, ceded the Pescadores, Taiwan, and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, recognized Korea's independence from China, and required China to pay an indemnity and offer commercial concessions to Japan. The military victories and treaty concessions were very popular in Japan, as they seemed to validate the direction the country had gone in modernizing itself in the previous decades.

Pages |