Pages |

Contemporary Music – Showa Period (1926-1989)

Beginning in the latter half of the twentieth century, Japanese traditional instruments (hereafter referred to as wagakki 和楽器) began to appear in new musical idioms including, but certainly not limited to jazz, free jazz, contemporary classical music, and various kinds of popular music around the world. According to scholar E. Taylor Atkins, the 1960s and 1970s represent the first major “boom” in the study of Japanese jazz history. It also represents a major “boom” in the study of contemporary music featuring wagakki.

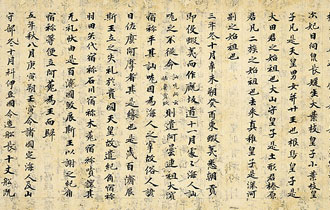

In the late 1950s and early 1960s composer Takemitsu Tōru武満徹 (1930-1966) began integrating traditional Japanese instruments into his film scores and musical compositions. While Takemitsu’s use of traditional Japanese instruments in his film scores and orchestral music is limited, nonetheless his landmark compositions such as “Eclipse” (1966) for biwa 琵琶 (pear shaped lute) and shakuhachi; “November Steps” (1967) a double concerto for biwa, shakuhachi and orchestra, and his film scores for Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962) and Akira Kurosawa’s Ran (1985) would reshape what composition would look like for composers both in Japan and abroad.

At first, Takemitsu, like many composers of his generation, was extremely apprehensive about writing for wagakki. During the World Wars, genres such as gagaku, noh, and jiuta were used for nationalist propaganda and recalled the memories of wartime Japan. Even fifteen years after the end of World War II, composers were not comfortable utilizing wagakki in their works. Takemitsu claimed he would not become interested in his own indigenous culture were it not thanks to American composer John Cage (1912-1992) and Cage’s studies of Zen Buddhism.

Takemitsu’s collaboration with shakuhachi virtuoso Yokoyama Katsuya 横山勝也 (1934-2010) and biwa virtuoso Tsuruta Kinshi 鶴田銀史 (1911-1995) helped pave the way to landmark compositions like “Eclipse” and “November Steps” that featured the shakuhachi and biwa. These two compositions are significant for several reasons: (1) this was the first time in history that biwa and shakuhachi performed together in any musical setting; (2) prior to 1966, few if any Japanese composers had written concert music that featured wagakki alongside Western counterparts; (3) both “Eclipse” and “November Steps” feature a significant amount of improvisation, granting the soloists a previously unheard of amount of performer agency and control in a previously strict and regimented style of music.

The shakuhachi style of playing in “Eclipse” and “November Steps” is informed by the genius of Yokoyama Katsuya. At the age of twenty-five, Yokoyama began studying with the legendary Watazumi-dōsō Roshi 海童道祖老師 (1911-1992), who had created his unique approach to Buddhism and shakuhachi playing, deeply rooted in meditation and intense physical exercise. Watazumi’s compositions were standardized by Yokoyama who formally established this type of playing. It is now commonly referred to as dōkyoku, “melodies of the way” (Keister, 2004). This way of performing is vibrant and gripping, using extremes of high- and low-pitched sounds, sudden shifts in tempo, and virtuosic technical passages that helped bring shakuhachi to the forefront of the musical world. This unique style presented an intense departure from all styles of previously existing shakuhachi repertoire.

At the climax of “November Steps,” Takemitsu gives the soloists graphic notation in the form of lines, numbers, boxes and various other shapes to convey the sounds he was interested in hearing. The notation is not related to traditional notation systems used in Japanese music or in Western concert music. As a result of this unique notational system

Tsuruta and Yokoyama…improvised their own cadenzas. In subsequent performance, Tsuruta wrote out her part and basically played the same way every time. Yokoyama on the other hand varied his playing each subsequent performance, especially the cadenza (Blasdel 2017, Kakizakai 2017, Samuelson 2017, Rothenberg 2017).

This was a truly unique moment in compositional history. Most performances of “November Steps” last approximately twenty minutes and, depending on the performance, the cadenza between the shakuhachi and biwa is approximately 8-10 minutes, nearly half of the entire composition. This shows a remarkable amount of trust on Takemitsu’s part, as well as the incredible combined skills of Tsuruta and Yokoyama.

Tsuruta’s transcription of the cadenza has been standardized and passed down to her students. Conversely, Yokoyama’s cadenza has not been officially transcribed since it was performed differently with each subsequent performance. Other shakuhachi performers such as Christopher Yohmei Blasdel and Kakizakai Kaoru 柿堺香 (b. 1959) have created their own interpretations by transcribing pre-existing recordings and then adding their own embellishments in an effort to emulate Yokoyama’s free style.

Takemitsu was attracted to the biwa and shakuhachi because of their sawari 触り, or the particular sound qualities of the instruments. For the biwa, it is the strong buzzing in the sound of open and fretted strings. For the shakuhachi, it is the subtle and constantly evolving timbral qualities within a single sound. The quality of sound is as important as the pitches/melodies produced and represents the core being of playing shakuhachi. Many of the sounds heard in traditional repertoire were inspired by sounds heard in the real world. For example, Takemitsu describes the sound of the shakuhachi as akin to the sound of the wind blowing through a bamboo grove (Cronin, Takemitsu, and Tann 1989.)

Works like “November Steps” represent a perfect marriage of two seemingly disparate musical worlds. Takemitsu ultimately made no attempts to create a unity from the soloists and the orchestra – he saw this as an easy way out claiming “Westerners, especially today, consider time as linear and continuity as a steady and unchanging state. But I think of time as linear and continuity as a constantly changing state” (Takemitsu 1995). By accentuating the inherent dichotomies and fusing those worlds through moments of silence, Takemitsu created a sonic world that feels simultaneously traditional and avant-garde and has inspired other composers and performers to leave the confines of performing traditional repertoire and gives them the freedom to experiment in new fertile grounds.

Another significant shakuhachi player is the late Living National Treasure Yamamoto Hōzan 山本邦山 (1937-2014), the foremost Tozan school shakuhachi player of his time. He was a prominent teacher and prolific composer and wrote film music and concert music featuring wagakki. Throughout his career Yamamoto collaborated with musicians such as Isaac Stern, Ravi Shankar, Nano Suratno, Wolfgang Mitterer, Jean Pierre Rampal, and Gary Peacock. In 1966 Yamamoto founded the shakuhachi trio Sanbon no Kai with Aoki Reibo II 二世青木鈴慕 (1935-2018) and Yokoyama Katsuya to increase the shakuhachi’s presence in contemporary concert music circles. To further accomplish these ends, he began experimenting with jazz artists as early as 1964, collaborating with Tony Scott on the LP “Music for Zen Meditation (and Other Joys).” He later collaborated with ensembles like Hara Nobuo’s “Sharps and Flats” and later participated in workshops such as Shoichi Yui’s “Opening Untrodden Spaces” performance workshops in August 1970. The three virtuosi, Aoki, Yamamoto, and Yokoyama, along with the great Kinko-ryū player Yamaguchi Gorō 山口五郎 (1933-1999) were the four “giants” of shakuhachi in the twentieth century. They stand as models for the generations of players that followed and did much to inspire the instrument’s gradually increasing popularity around the world.

Pages |